Contemplating the mortality and fragility of life through artistic mediums, whether music, painting, poetry, literature, what have you, has been a popular theme and a very necessary philosophical topic since evolution has granted us the ability to gaze into our navels and contemplate such things. It is the one undeniable constant that must be faced, despite our sometimes obstinate avoidance of the topic. Yob has built quite a discography through this questioning, developing a deeply affecting blend of doom and beauty that has elevated the form through Mike Scheidt’s desire to more fully understand what living truly means. The band’s latest album, Our Raw Heart, is certainly a direct continuation of Scheidt’s vision, albeit with one very dramatic difference. He now has a very definitive basis for these questions.

Much has been written Scheidt’s battle with diverticulitis, and just how close to he came to death. It is undeniable that such a cataclysmic event must absolutely affect one’s view, both externally and internally, and it is equally undeniable that this affect must creep into the artistic process. Facing the fragility of the human body and the finality of existence is terrifying stuff. It is nigh impossible to separate the idea of Scheidt nearly dying with the spiritual intensity Our Raw Heart’s seventy three minutes. It seeps into both the oppressive heaviness, such as the crushing “In Reverie”, and the shimmering ache of “Beauty In Falling Leaves” equally.

However, with no slight to the tribulations and pain that he has gone through, focusing on this aspect of Our Raw Heart gives short change to the fact that Mike Scheidt has been both aiming for and achieving this level of spiritually seeking doom and beauty for some time now. It’s as apparent on the band’s breakout 2009 album The Great Cessation as it is on Our Raw Heart that Scheidt has been searching for answers to much deeper questions than usually asked in the genre.

“Here’s the thing, I’ve talked about it a lot. It’s so high profile now. It’s something that happened to me that was huge. Every single human being is going to have their own version or versions of it, something where their mortality is going to become undeniable, whether that means they exit this life at that point or somewhere down the line will be determined. I don’t want this to be the ‘illness record’, where it’s a story line that can’t be separated aesthetically or internally. Certainly the illness had an affect on the record, but it’s also just a symptom of how every album comes out in that it was written from the place, the raw material is where we are at as a band. In this particular instance, part of of it, not all of it but part of it, was around whether we were even going to be able to be a band anymore. But I don’t want to bludgeon people endlessly about this illness when it’s pretty much common knowledge, to the point that it’s an exhausting part of something that actually ended out very joyous.”

It is borderline cliché to say that a band’s album is not just a collection of songs but rather a journey. There is, however, no way around applying this idea to Yob albums. Whereas the band has always been a deeper example of the genre, 2014’s Clearing The Path To Ascend and Our Raw Heart are the very definition of ‘next level shit’. There is a depth and maturity in their music that elevates their work above the rote bludgeoning of demonic weed smoking and open E chords. The empathetic connection between instruments is unbelievable, and it is impossible to avoid yet another cliché in that there isn’t a wasted note to be found. Yob has been expanding their palate with each album, employing beautiful textures alongside the more traditional doom to incredible affect on the aforementioned “Beauty In Falling Leaves” and especially the title track. Bassist Aaron Reiseberg and drummer Travis Foster are absolutely essential to these songs, one of the tightest and most expressive rhythm sections going today, a perfect foil for Scheidt’s spiritual quest.

“What’s interesting about that, and not everyone is aware, but if you google Yob Essence, there’s a song from The Unreal Never Lived sessions that didn’t make the cut because it was such a different kind of song. That song was actually really the beginning, over ten years ago, and it’s as beautiful and emotional and exposed as anything we’re doing now. We’re better at it now than we were then, but it’s all cut from the same cloth. If you look at songs like The Great Cessation or Adrift In The Ocean or even Catharsis, there is a lineage of these beautiful moments. I just think we’re getting better at, and more clear, at what it is that we’re aiming at.

I’m writing all the time, and I bring it to Aaron and Travis, and when all is said and done, only about ten percent of it makes the cut. It’s the three of us together running through things, and you can listen or play through something by yourself and you have one impression, but if you bring in just one other person, you feel it differently with their attention there. With Aaron and Travis, our collective attention really makes the decisions on what becomes what, and if something resonates with us it’s just a matter of hammering it out. Sometimes things go down exactly as I’ve arranged them, some things morph into something else, and then over the life of the song after we record it, the three of us playing these songs over and over in myriad environments is also a component of what makes those songs become the living, breathing, continuing things that they are that then carry into the next album. Aaron and Travis are integral, there is no separation. I get a lot of the press, because I can articulate the concept of the band because it sort of springs out of me to begin with, but I write for Aaron and Travis, I write for Travis’s right foot and his weird lag, that’s just a breath behind where the beat would be. It’s very much one thing.”

One aspect of Yob’s new album that is intrinsically laced with Scheidt’s illness is the newfound dynamic vocal range. While he has always displayed more range than most in the field, there is a definitive difference in his performance on the new material.

“I’ve done a lot of studio work and collaborations between the last album and this one, and vocals are the thing that I work on the most. I practice them way more than guitar, and I probably should find a better balance with that, but I’m just enamored with my favorite singers, and what makes them great. I’ve done enough training with Wolf Carr in Seattle that I’m starting to get glimpses of why those great singers are great. But on top of that, speaking to the illness, I wasn’t able to sing for six months and all of my surgeries and incisions were in my mid-section. I couldn’t put weight or pressure on my mid-section because I was incised in so many different places, both internally and externally. My diaphragm, the muscles between my ribs, my lungs, my entire mid-section had atrophied a bit. So when I was given the go to start singing again, I had to go about it very gingerly for fear of herniating those sites. Wolf had been teaching me about these various other resonant chambers in the body where a person can grab timbre, different kinds of color and expression, and I understood some of what he said. Some of it went over my head, much like anything. When I was rebuilding my voice, I just didn’t want to make bad sound, so I began sending air to other places in my nasal cavity and chest, just trying to find other ways to sound good. As I started getting my diaphragm and ribs and muscles and air back, getting back to the place that I was, I had all these other places to sing from that I didn’t have before. I mean, given how compromised my mid-section was, I feel like I have a set of skills with my voice that I didn’t have before. I think being forced to stop for that long and having to rebuild, that’s not something I would have voluntarily done, but the result, at least for me was very significant. I still have a long way to go, believe me, and I won’t be writing any singing method books any time soon, but I was able to do a lot of experimenting with things I didn’t have before, and it was fun.”

Art is a very subjective medium, much to the benefit of fans across the spectrum, and it is a very easy thing to fill columns with what appeals to your personal tastes and what does not. It becomes more difficult to ascribe words as to why things appeal or don’t appeal. It becomes even more difficult to ascribe meaning as to why something is more profoundly affecting than another. Ostensibly, Yob haven’t been reinventing the wheel since their conception. They haven’t strayed much from their artistic vision over their last few releases. Still, it is undeniable that they have reached new heights over the last several years. Scheidt, Reiseberg and Foster have a organic chemistry that allows them a freedom and malleability over the concept of genre that not many bands ever achieve, and Yob’s songs are imbued with a spiritual depth many band’s can only dream of achieving, an emotional heaviness that feels neither forced nor overtly intellectual. Scheidt manages to tap into the overwhelming questions of mortality and fragility in such a personal way as to shed the morbidity of the discussion, opening the path to an honest conversation about what defines this life and how we choose to live it.

“I’ll tell you man, talking about this sort of thing, the artistic process, intent… can get pretentious and annoying really fast, even if it’s sincere. It’s difficult not to use comparative statements, which are not necessarily things that I feel. To say that our band’s music is X and another band’s music is Y… I think X and Y are equal and important, and I subscribe heavily to both X and Y.

That being said, this band from day one, it was a symptom of loving music and having been a long time musician, and also being on a spiritual path. I use the word spiritual in quotations as that word has lost some of it’s mojo, but just the path of asking a lot of questions and getting to a place where I felt like I couldn’t drink the Kool Aid anymore and being just driven by our creations. Taking our own creations and beating ourselves over the head with them. And yet, these creations, they all come and go. Nothing lasts. Everything changes, everything is interdependent and built upon something else, this continuous flow of whatever it is that isn’t what we think that it is and it’s not what we see that it is. Within that, there’s drama and hurt and love and disappointment and arrogance and jealousy, all these things that run through our system.

This music and what I’ve always written about is my own feet-in-the-mud, falling-on-my-face experience, but wanting to have a personal relationship with something that feels closer to reality as it is, before thinking, before definitions, to have some expression within that. All of these albums later, it’s no different. And this is where it sounds like it could be pretentious, because that’s a lot of hoopla and a lot of, maybe, new-agey garbage, and yet, I’m holding my hand in front of my face right now and calling it my hand, and you have your imagination of a hand, you have them too, but I don’t know what the fuck this thing is. Really. I have no idea why or how I can do any of this stuff. I just can’t take that for granted. As time goes on, I just feel like I’m getting closer and closer to… not trying to hone in on that but this thing about how the struggle of living and grappling with mortality and fear for my children and the world they inherit, how those things feel and how they feel in a way that’s not being numb. It’s not being dumbed down, not having some substance or distraction poured on it. To really look at it to the best of my ability, and not in comparison to anything else.

Nobody was supposed to hear this shit. This was a band that nobody cared about, really. We did this shit for ourselves. It was about the things we wanted to write about, not winning a contest or be in some cool club, and once again, that’s a comparative statement. There are lots of good reasons to make music, and many of them can be to live out your dreams and be ambitious and go for it, and I support all of it. There’s nothing wrong with any of that. I’m a skeptical mystic, and as a result I question everything ad nauseam. I know that there are lots of things to work on and this life, especially post-illness, is important to me to feel like I did my best.”

Facebook | Instagram | Twitter | Website

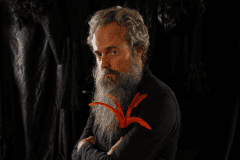

Photo: Orion Landau

Social Media