Progressive rock, a form of psychedelic rock given to complexity and bombast, dominated the airways and arenas in the 70s, allowing groups of bearded musicians to live out their grandest fantasies, from playing synthesizers upside down to wearing capes in public. But prog has largely disappeared from the modern music landscape as a coherent cultural force.

Perhaps that’s because prog was absorbed by everything else. Its DNA is easy to see in modern rock bands like Radiohead, the Dirty Projectors or Sigur Ros, and prog songs have been widely sampled by hip-hop artists. Even country has taken a look at progressive rock and seen some things to like about it – it’s easy to hear the connection between groups like Soft Machine and Gong and Sturgill Simpson’s Metamodern Sounds in Country Music.

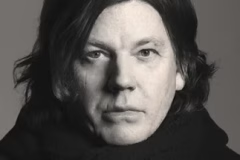

But once, giants roamed the earth, and groups like Emerson, Lake and Palmer and Yes filled arenas eager to listen to extended drum solos and synthesizers so large they get their own hotel rooms. The Show That Never Ends, written by Washington Post political journalist David Weigel, tells the tale of a time when groups like King Crimson, Pink Floyd and Genesis made era-defining music that aspired to be something new, and why that hubris came crashing down.

Prog’s critical and popular reputation has recovered a bit of late, but it wasn’t too long ago when bands and fans were once again at the “back to basics” part of the musical cycle, when neo-garage bands like The Strokes and The White Stripes were at the top of the charts. But according to Weigel, part of what fascinated him about prog was what gets taken up and left behind at different times, especially in the way people would admit a liking for prog only after laying out their hipster bona fides.

“There was this appreciation that people would admit only after they listed the cool bands they liked. I think what I found interesting was not that it was influential note by note in the music. Something like punk obviously has more resonance than the last rock movements that were popular,” Weigel said about the status of prog in the modern world. “I was interested in what they didn’t use. Why people didn’t harp back to extremely ambitious 20 minute song suites and these things that could be characterized as pretentious, why they had never been picked back up. I discovered around the same time revivalist bands and progressive bands, ones that still existed like Porcupine Tree that were carrying the torch.”

Like a lot of people, Weigel was introduced to the music of an earlier generation by word of mouth, whether from an older record store clerk or, in Weigel’s case, Mark Prindle’s (since retired, but archived) record review site, which reviewed a wide range of music, including prog. “He reviewed these bands I liked like AC/DC and metal bands I had never heard of,” Weigel said, “but also had this big soft spot for progressive music. I was interested in Yes and I wrote down a list I think of what he reviewed that sounded interesting to me.”

That nearly boundless feeling of exploration is part of what makes exploring prog so rewarding. Genesis don’t sound like King Crimson, Camel, or Van Der Graaf Generator (or even like itself, album to album). What makes prog such an interesting subject is how large and amorphous it can be. That very breadth posed a question for Weigel as he was putting together the book: how do you define what prog is?

“When there’s a big topic, you want to make sure that you convey what the people who hear the topic thinks is important,” Weigel said. “I do the same thing. A lot of talking to people on what they consider to be key. I base it on that. I didn’t have a list on the wall.”

The book’s genesis (ahem) began as a series of articles when Weigel was working as a reporter for Slate. The book reads like a series of interleaved articles on subjects covering a great scope of personalities and eras, all in a readable and approachable form. Weigel’s research included an incredible deep dive into magazine and newspaper articles from the era: record reviews, interviews, gossip and descriptions of shows, from archives like the Library of Congress, the British National Library and other smaller, private collections.

“I had thousands and thousands of these documents and I read them all,” Weigel said. He also conducted dozens of interviews with musicians, weaving all of that into a coherent narrative. “I did this all holding this job, first with Slate then moving over to Washington Post,” Weigel said. “It was mostly done by the time I got to Post. There were times I could take a few weeks off and there were times I couldn’t. There were a few interviews I had to do just in the middle of my workday.”

Words by Aaron van Dorn

Website | Twitter

#Gaza

#Gaza

Social Media